For decades, narco corridos, songs that narrate the lives and exploits of drug traffickers, have been a big part of Mexican culture, but also very controversial. While fans argue that they reflect reality, authorities claim they glorify crime and contribute to a culture of violence. Some states in Mexico and the U.S. are stepping up efforts to keep artists from singing this type of music, which has started a big debate about freedom of speech, culture, and public safety.

Narco corridos come from traditional Mexican corridos, which used to involve stories about heroes and revolutionaries. But when the drug war got worse in the 1980s and 90s, these songs started focusing on a new kind of figure, “the drug trafficker.” The lyrics began to talk about drug routes, fancy lifestyles and violent fights between cartels.

“These songs praise people who’ve done damage to Mexico and its people,” sophomore Camila Ortiz said. “I think banning them shows the change the government is trying to make.”

Musicians like Los Tucanes de Tijuana, El Komander and Chalino Sanchez (often called the father of narco corridos) became famous by turning real crime stories into popular songs. But with that fame came danger. Several performers have been killed for choosing the wrong side or simply for singing about the wrong people.

In the past year, several Mexican states, including Sinaloa, Baja California and Chihuahua, have either banned public performances of narco corridos or imposed heavy fines on artists and venues that play them.

Local people argue the bans are necessary to avoid cartel influence, especially among youth.

“I’ve never listened to this type of music, but banning it seems like a way to protect people,” junior Jonathan Bermudez said. “We can’t allow criminal culture to be normalized through music.”

South of the border, U.S cities with large Mexican populations are beginning to follow suit. In places like Phoenix, Houston and Los Angeles, some venues are starting to refuse to book narco corrido artists in fear of public pressure or cartel-related violence.

On Jan. 5, 2025, threat messages from the cartel were found in Sonora, Mexico, against the singers Natanel Cano, Tito Torbenillo Jr. and Javier Rosas.

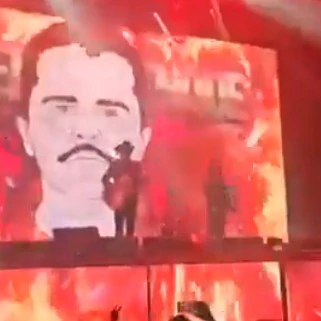

Law enforcement in the U.S has also taken notice. They’re beginning to revoke visas from artists who project cartel culture. On Apr. 1, 2025, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau confirmed that the work and tourist visas of Los Alegres del Barranco were revoked after projecting images that glorify the “narco.”

“I feel like everyone should have the option to listen to what they want,” sophomore Jennifer Melecio said. “It doesn’t really harm anyone.”

But others argue the romanticization of traffickers creates a dangerous environment.

“For example, Luis R. Conriquez’s concert in Texcoco ended in chaos,” Ortiz said. “All because he let his fans know that he was quitting the singing of narco corridos on stage.”

As the bans grow more widespread, artists are adapting. Some are changing lyrics, branding their music as “corridos belicos” or “corridos tumbados.”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo organized a contest (Mexico Canta) where the goal is to inspire young people to participate with various types of content, including music, to set an example in society. Most Mexican artists are those who influence violence and crime in their music, but not all. Other talented Mexican singers involve creativity in their music, such as Julieta Venegas, Ximena Sariñana, Kevin Kaarl, etc.